Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.

– Albert Einstein

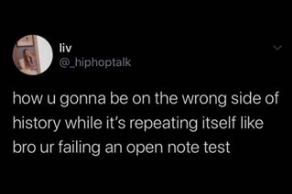

The moment that we’re living right now in the United States epitomizes why historical thinking must be at the heart of teaching history. Between COVID-19 and George Floyd, our country is acting like a crazy person, isn’t it? We keep doing the same thing, thereby failing an open book exam. (Thank you, Instagram, for your wit and brevity.)

History is an open book exam. To teach history isn’t to drill facts like the 1918 flu pandemic or systemic racism into a student’s head for some standardized test. We’re watching history repeat itself. We owe it to our youth to teach them what not to do because we have this data at our fingertips that says, basically, Hey, folks, stop doing this. We know better, and we must do better. Don’t get me wrong – I’m not talking about historical hubris. I’m not saying do better because we think we’re better. I’m saying do better because we know better. It’s a huge difference.

We never really know history, and what we do know will always be imperfect, but no matter what, the present and the past are interlocked and very much co-dependent. History is people, and people are complicated. Current affairs are complicated. History is a means of teaching students how the collective we got here. If we don’t understand how we got here, then we’re forever going to struggle with our civic duty and responsibilities. Not to overstate the obvious, but the last thing we need is a young generation of followers who don’t ask the hard questions and get to the root of the issue because, after all, teaching history is teaching students how to solve problems.

Sam Wineburg talks about a growing historical ignorance, which, I think, may be exacerbated by standardized testing because students are taught to pass a test, not think and understand. In the current state of affairs, a historical date or event or a famous figure is moot if a student doesn’t understand a deeply complex concept like systemic racism, which history unequivocally shows and proves is a very real thing. We can’t dumb down our education if we have any hope of not repeating the past’s malfeasance, but we need to start with ensuring that our primary and secondary school teachers understand history and the power and value of historical thinking. It’s the only way that we’re ever going to affect positive change and leverage historical thinking to its fullest capacity.

It’s easy to talk theoretically about affecting positive change via historical thinking, but how do we actually do it? Start with teaching students that history is all about interpretation because that’s the truth. But interpretation isn’t just opinion – it’s about exploring historical evidence, cause and effect, context. It’s complicated! And that’s what students need to understand. History isn’t about what you know and how much you memorize; it’s about how you think. It’s so basic yet so often overlooked, which, again, I circle back to current affairs. Our past is a direct line to our present. I hope that, for once, we don’t fail this open book exam because the answers are right in front of us.

One comment on “What elements of historical thinking have remained at the heart of history teaching over the decades?”